A Dangerous Beauty:

The Sculptural Works of Tammy Ballard

Pablo Picasso once stated, “The artist is a receptacle for emotions that come from all over the place: from the sky, from the earth, from a scrap of paper, from a passing shape, from a spider’s web.” From Monet’s haystacks to Warhol’s soup cans, artists awaken hidden beauty in the unexpected, the accidental, or even the banal. But artistic expression has always been a dangerous beauty—it has the power to challenge our opinions and to shape our perceptions, to steal our attention and to lead us into the most secreted corners of our minds.

We have conversations with works of art, conversations that often reveal more about ourselves than the artwork at which we are gazing.

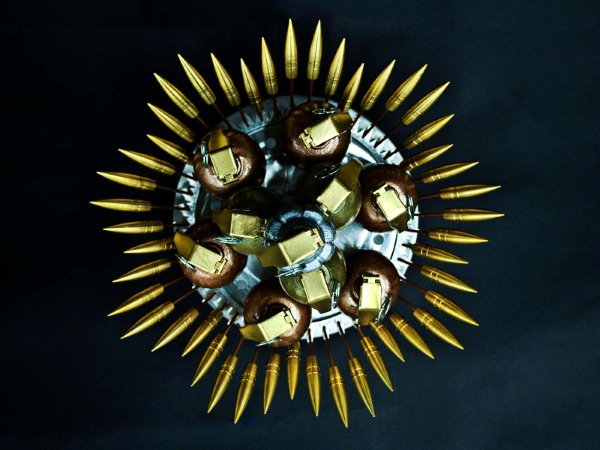

Within the context of artistic conversations, the sculptural works of Tammy Ballard like to ask questions. On an aesthetic level, Ballard’s assemblage works are tightly composed with classical proportions and harmonious balance. The artist creates strong visual interest through the interplay of polished and matte surfaces, as well as the intricate association of contrasting shapes. The viewer wants to reach out to touch sculptures like Blow . . .Make a Wish, if only to satisfy his or her tactile cravings; but upon closer inspection, one realizes that the delicate edges of dandelion fluff are actually the sharp metal 50 mm brass bullets.

Ballard’s current series, Visual Voice, stems from the twentieth-century tradition of Assemblage Art, a style that has roots in Dada, the seemingly “anti-art” style born as a reaction to the First World War. Nearly one hundred years ago, the ready-mades of Marcel Duchamp opened the door to artistic experimentation that would extend far outside the conventions of traditional media. Mid-century found-object reactionaries would incorporate a range of unconventional materials into their works; such as Louise Nevelson, who created large-scale installations out of wood objects scavenged from the streets of New York. She then painted them uniformly in shades of white or black.

Like Nevelson, Ballard scavenges to find her materials, but rather than assembling wooden dowels, finials, and other domestic bric-a-brac as Nevelson did, Ballard takes her inspiration from less organic materials. Scraps of metal, chips of aluminum, and fragments of barbed wire can be found alongside dog tags, medical tools, uniform buttons, and, of course, bullets. Unlike Nevelson, Ballard does not shy away from powerful religious symbols—Forbidden Fruit, Tree of Life or Death, and Burning Bush each transform recognizable Judeo-Christian emblems into disturbingly calculated assemblages of bullets, grenades, and metal fragments.

In some ways, Ballard seems like a better Dadaist than the original proponents of the style meant to refute the society that produced “the war to end all wars.” But perhaps that is where the connections end. Although she references ideas related to politics and religion, Ballard’s works may be best understood within the construct of industry. By juxtaposing organic with industrial, natural with artificial, Ballard’s works reference the paradox of modern society. But that is not to say her works are symbolically linked to Futurism, the anarchy-driven movement of the early twentieth century that promoted war and cultural rebellion. Ballard is not necessarily putting forth a specific agenda; instead, she is using her works to probe deeply into powerful concepts and queries.

In an era when our portal to the world is our computer screen (they gaze at our faces more than our loved ones), when our most intimate companions are our phones (they hear all our secrets) and our electronic gadgets (they know the melodies that makes our hearts race), where do we find solace? Where do we go to ask the most important questions of life? Sometimes answers are found in the most unexpected of places.

.jpg)